Midwest Sandbox

In his book, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States, Kenneth T Jackson notes that “This book is about American Havens. It suggests that the space around us – the physical organization of neighborhoods, roads, yards, houses, and apartments –sets up living patterns that condition our behavior.” Growing up in the South Florida suburbs, I was only given a small slice of creative freedom. The Florida suburbs are designed for a specific type of buy-in.

HOAs require trashcans to be hidden at all times, or else a fine is assessed to your family. Hedges are trimmed multiple times per week, in order to hide all imperfections of new growth. The physical organization of the suburbs I grew up in force creativity and expression to remain indoors and unseen. I was conditioned to believe that my physical surroundings had a power over my creative mind, and that I was banned from exploring the inner-workings of the machine. I didn’t realize this until I left. I couldn’t have.

Essential human mechanisms were hidden in favor of a quality of life that champions projections of wealth and social status. I’m thinking here about hidden power lines, armies of contracted landscapers, and amenity-driven development. There is nothing ugly about it. Most of the midwest is not like this. Infrastructure is older and exposed to more elements, causing faults in the construction of buildings to shine through. There is trash on the streets. Power lines sit mangled upon leaning poles. It is more honest here.

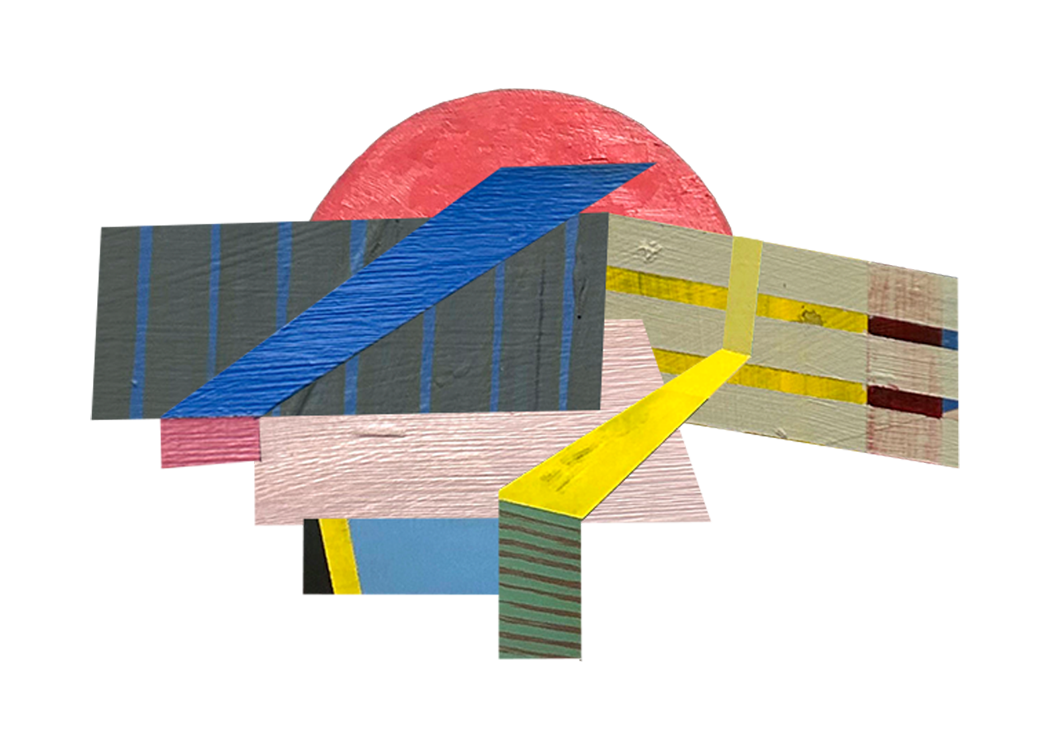

Exposure to the grittiness of Milwaukee unlocked a core component of my personality that couldn’t develop properly in Florida’s rinse-and-repeat suburbs. And that key component is that I need space to play. I love seeing traffic cones as sculptures, electric meters placed in ridiculous spaces, and the grime of the streets sprawled out in front of me. There are stories and histories that are naturally uncovered in midwestern cities that won’t ever see the light of day in the Florida suburbs. I could never make the type of work I’m making in any other place.

I have spent the last three years documenting my exploration of the city. I run the Instagram archive account @_.dissolve with my studio mate, Callie Kiesow. The goal of dissolve is to document the here and now, with the hope of capturing authentic street life. I also collect material, detritus, objects…whatever you want to call it. These materials make their way into my work, sometimes literally and sometimes as hidden surfaces or structural moments. My collection of materials and ways of making have infiltrated the worlds of my artist friends and grad cohort. I love getting these types of messages.

The collective essence of the midwestern city asks us to consider the past. It allows us to truly see the consequences of our existence. In a way, I feel called to document what is really going on. My work in the studio reflects the ways I am seeing and interacting with my urban environment.

In the aftermath of the shift to remote and hybrid work, I think the way of the city street has been lost on a lot of people. I was at the vet a few weeks back, and the road outside of the office has been under construction for a while. As I was above to leave, a man walked in holding a cup of dog pee. He looked at me and then the receptionist and said “It’s nice to get out once every couple of weeks to see the progress on the neighborhood. It’s really coming along.” Like that is crazy to me! There is such a privilege that comes with a separation from the grittiness of it all.

They are starting to build these apartment complexes that have everything you need to survive. Indoor parking garages, gyms, pet parks on the roof, Amazon drop-off locations, demo kitchens, movie rooms, co-working spaces, golf simulators, yoga studios. It is like a “kit” of life that is handed to you and you never have to leave. This is a lot like the feeling I got in Florida. And I do understand that there is a target audience for that. The people that choose to live in those places believe that that is where they are supposed to live. This is a sociocultural and political thing. This is their truth and reality. And that is okay. But I would much rather be scouring the streets only to stumble across an old exposed facade that has been around for 150 years and is still kickin.